Veni, Vidi, Vici

After winning a civil war that rocked Rome in the first century B.C., Julius Caesar proclaimed three of the famous Latin words in history – ‘Veni, vidi, vici’ which translates to ‘I came, I saw, I conquered’. If the tigers were to speak our language, they would probably say the same after conquering unknown lands.

This story is not just of a single tiger or the place where he was born or the kingdom he’s trying to establish. It is a story of free ranging tigers colonizing the forests, naturally engineering the forests and the climate subsequently and the efforts of stakeholders in assisting, preserving, and undoing the decades or centuries old damage done to the ecosystem by the earlier generations of humans.

The central Indian landscape was perhaps the most diverse of the Indian subcontinent because it connected the genetically diverse tigers of the colder North with the tropical South. Though all Indian Tigers are classified under the same taxon, they exhibit different traits, even in terms of physicality, when compared with one another across the vast Indian latitude. For example, broadly speaking, as per the Bergmann’s rule, the larger individuals of the species are generally found in the colder climate (or towards the poles) and the smaller are found in the warmer climate (towards the equator).

With many fertile rivers flowing across the Central Indian scape, making the land highly arable, the human population exploded in these parts, effectively reducing the tiger-scapes to mere patches with almost no connectivity. The corridors that used to be vast swathes of inviolate spaces are now human dominant landscapes.

The biggest challenge of tiger conservation is not the management of the protected area, but the provision of the migration corridor to maintain genetic diversity and flow of surplus populations.

More than 70% of the world’s last of this species lives in India in many of the 52 tiger reserves and a fewer of the 564 wildlife sanctuaries. While the tiger population is currently estimated at 3000, the forests of India can hold many more tigers. Because it is a charismatic and keystone species, and a part of the prestigious project tiger, tiger forests receive the utmost protection, especially from illegal occupation of lands, grazing, mining, etc.

Johnnie, Walker and Jack

Johnnie was born in April 2016 to Pilkhan tigress and sired by the dominant tiger, Star, in a wildlife sanctuary known as Tipeshwar, often referred to as the green oasis of southern Vidarbha, with atleast four rivers passing through the sanctuary. Tipeshwar was made home by Star male who migrated from further North. Star sired most of the tigers in Tipeshwar.

Prior to 2010, there were no records of tigers in Tipeshwar. Subsequently, 3 tigers were known to have inhabited the forests of Tipeshwar. All the tigers in Tipeshwar are believed to have been born from one matriarch, the mother of Talaowali (lake female) and Pilkhan tigress, who are now at the helm of increasing their tribe.

Situated in the south-eastern part of Vidarbha, the 148 sq. km Tipeshwar went from being a sink (collecting surplus population) reserve to source (generating tiger numbers) reserve, within a span of 8-10 years, with effective protected area/forest management, despite the issues that plague the more stringent tiger reserves existing in Tipeshwar and the adjacent Painganga WLS as well.

As recently as 2021, both Tipeshwar and Painganga WLS have received a good rating in the Management Effectiveness Evaluation (MEE) of National Parks and Wildlife Sanctuaries in India 2020-21. Parameters such as comprehensive management plan, participation of stakeholders in planning processes, habitat restoration programmes, effective protection strategy, organized and effective personnel, etc., are well met. With many resident tigers, the indicative species, Tipeshwar, is a story of conservation success.

With Tipeshwar sprawling with tigers, the adjacent wildlife sanctuaries and tiger reserves are bound to receive the surplus or migrating population. Tigers have migrated to different parks. Painganga WLS will soon have its own population, thanks to the unflinching efforts of stakeholders, dedicated officials, visionaries, and diligent ground staff. The last known tigers vanished from Painganga decades ago, before Johnnie and his mate Indu (I-mark female, from the lineage of Maregaon – Pilkhan tigresses) made inroads, from Tipeshwar.

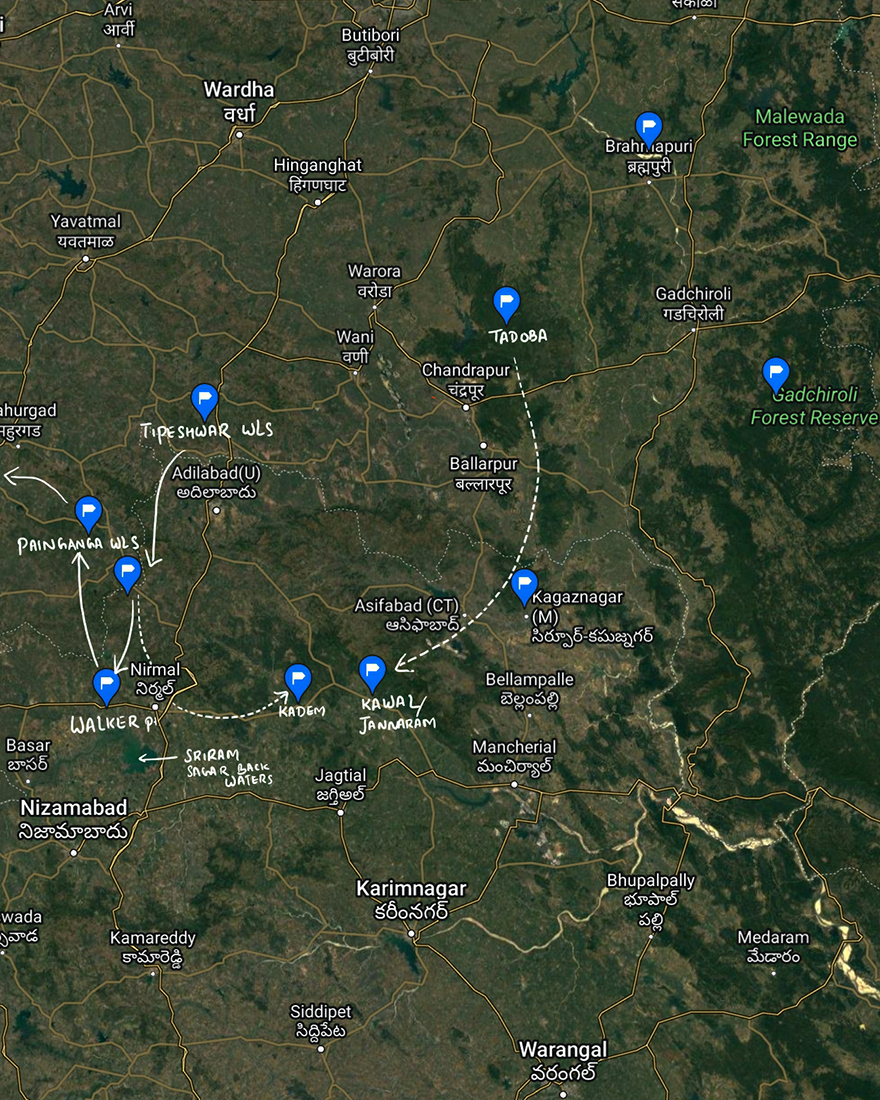

Erstwhile, Painganga was a stop for transiting tigers, such as Walker, that are known to have used the migration route till Nirmal (as seen in the map), which blatantly talks about the connectivity with Kawal Tiger Reserve, one of the biggest sink reserves for surplus populations and the terminus for tigers from the Central Indian landscape or even a corridor to reserves in Chhattisgarh such as Indravati Tiger Reserve and further East or North-east.

But tigers return from or vanish at Kawal which is no more inviolate due to a plethora of reasons such as rampant cattle grazing, conversion of forests to podu cultivation lands etc. Ironically, one of the actionable points of the MEE report is to strengthen the corridor between Tipeshwar, Painganga and Kawal TR. One of the pressing points for the gap in understanding conservation, between the adjacent states of Maharashtra and Telangana (or A.P.) seems to be a weak people’s interface on the protected area management (and general idea of wildlife amongst the public), also as highlighted in the report.

Since the time Tipeshwar became a cradle for tiger populations, Kawal was expected to receive the surplus tigers. Many return or vanish without a trace, but the whereabouts of a few are still known and that itself is a horrifying story, of Kawal, which remains tiger-less to this day, despite attaining the status of a tiger reserve more than a decade ago.

The dotted line indicates the probable migration corridor, while the continuous line indicates the path taken by Walker.

The dotted line indicates the probable migration corridor, while the continuous line indicates the path taken by Walker.

In February 2019, T1C1 (Walker) and T1C3 (Jack) were collared, as part of the dispersal pattern study programme. Walker left Tipeshwar in June 2019 and walked along the borders of Maharashtra and Telangana, reaching as far as backwaters of Sriram Sagar Project, in Nirmal. This is the traditional migratory route of tigers to Kawal via Kadem. Walker retraced his path and reached Dhyanaganga WLS via Painganga WLS, covering a total distance of 1300 Kms in what is said to be the longest migratory distance by any tiger. His current whereabouts are unknown.

Jack seemed to have settled in Mathani area of Tipeshwar for a while, before moving out or being evicted by the dominant male, Star – Jack’s own father.

Johnnie (T1C2 at Tipeshwar and PNG-T1 at Painganga), the uncollared one was obviously less reported till he surfaced in Painganga WLS in October 2019, where he was first captured on trap cameras. By early 2021, Johnnie was joined by Indu (I-mark) female (PNG-T2 at Painganga) and they became the first tiger pair to be recorded in the sanctuary after a hiatus of 25 years.

While few tigers have maintained discreet migration and hunting patterns, with their presence only being detected or known from the cattle kills along the corridors they moved, a few others weren’t as lucky.

A female cub from the third litter of Talaowali (Tipeshwar lake female) moved away from its family and was seen along with the contemporary litters of Pilkhan (3rd litter) and Maregoan (1st litter) tigresses, for a short span of time. Packs and Clans are not a feature of tiger world. Possibly, the sense of independency creeps in only after tigers reach subadulthood (around 2 years of age). The very same female created a conflict situation along the fringe villages of Andharwadi, Kopamandvi, Kobbai and Sunna. In an unfortunate turn of events, this female cub was responsible for the death of the mother of a tiger tracker and guide from the village of Sunna on 18th September 2020. The tigress was captured later and shifted to Gorewada rescue centre, Nagpur (where it spends the rest of its life in captivity).

With tigresses across generations delivering cubs, and raising them to subadulthood in the protected Tipeshwar WLS, a few are bound to make inroads to Painganga, if not caught in the death traps of poaching, electric fencing, poisoning etc. The tigers are not falling prey to the death traps in protected areas, but are migrating, which only signifies the need of strengthening the corridors. These corridors will also ease the pressure off the source reserves and populate the sink reserves, while also adding to genetic diversity (hoping that tigers from different sources might collect at one sink and the newer generations might retrace to the source).

As far as the story of Johnnie goes, we are only hopeful that history does a repeat and Johnnie does a Star, populating Painganga and providing a source for Kawal Tiger Reserve.

Note: In the December of 2018, we named the three cubs of T1 aka Pilkhan female – Johnnie (J-mark on the neck), Walker (W-mark over right eye) and Jane. Jane was the smallest of all, and we mistakenly identified it as a female. The name was later changed to Jack (J-mark over left eye), after ascertaining its gender (as a male). Walker was the independent one and the first to leave the gang. Johnnie and Jack were together for a while before they parted ways. Knowing that Walker went on the longest migration and seeing Johnnie again after a recess of 4 years, in a different park are exhilarating because these tigers are making their own safe pathways to inviolate areas where they dominate and even probably save the forests (that are not legally protected areas) and even promulgate there, leaving us with an optimistic streak of such migrations in future.

- Suggested reading