Tigers – Then, Now and Forever

The modern-day tiger is believed to be a sister taxon of Panthera zydanski that seemed to have lived around 2 million years ago. The Youngest Toba eruption, a super volcanic eruption occurred 75,000 years ago, causing a genetic bottleneck from which today’s populations of humans, tigers, cheetahs, East African chimpanzees, Bornean Orangutans etc., recovered (thus the low genetic variance).

The Tiger, however, arrived in India in the late Pleistocene epoch, towards the end of the ice-age, around 16,500 years ago, from Greater Sunda Island area (present day Indonesia). Tigers existed in far-east and south-east Asia 30,000 years ago; South China tiger was one of the earliest, amongst modern day tigers to roam Earth.

Tiger has been an important emblem since the Indus Valley Civilization (on the Pasupati seal) to Chola, Pandya, Maurya and other empires all across the country. The mention of tigers is in Vedic literature as well. However, prominent accounts of the tiger were present since the Mughal era, particularly of the shikar, the big-cat game. It wasn’t an uncommon practice for the kings prior, to go on elaborate hunting trips, but the Mughal era heralded a new technique – gun powder for hunting big game, and for centuries of indiscriminate killing by subsequent rulers as well, this went on to bring an ecosystem of animals close on the heels of extinction in India.

Part-I

The Mughal chapter

Babur established the Mughal empire after the first battle of Panipat in 1526, utilizing the Ottoman artillery tactics, the same that the Ottomans successfully employed in the battle of Chaldiran in 1514 against the Safavid Iranian empire; the artillery techniques that weren’t known to Central Asia till then and took over the elephant warfare as the dominant offensive strategy, then.

The artillery that Babur brought with him to ‘Hindustan’ and also preluding the age of gunpowder were not only extensively used in decisive battles against the local kingdoms at that point of time, but also gave birth to a new game – hunting of megafauna, even more efficiently and in greater numbers.

Mughal emperors and statesmen used the matchlocks known as Toradar (based on the Portuguese Matchlock Musket) and other weapons for hunting. There are no clear records of Babar or Humayun indulging in this bloody sport, but the subsequent emperors, Akbar, Jehangir, Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb are known to have patronized the sport of hunting Tigers, Lions, Cheetahs, Deer and so on.

Abul Fazl recounts the tales of Emperor Akbar, who pioneered the sport of hunting big cats in ‘Hindustan’ in ‘Akbarnama’ and so does Emperor Jahangir about his own hunting exploits in ‘Tuzuk-e-Jahangiri’. It was not only a past-time activity but also a politically motivated scheme to showcase the local nobles and the chieftains the superiority of Mughal power and dominion over the stronger forces of nature and also the extension of Mughal friendliness by allowing them to participate in the hunts alongside the Emperor, thus yielding their support for the Mughals.

Most records recount of tales of Mughal Emperors and other contemporary kings killing Tigers in hundreds or a few thousands only; a far too lesser figure than what would supersede the Mughal imperialism.

The British chapter

The British introduced superior fire-power in terms of armaments (of course to strengthen their own armies). India became the largest producer of ammunition, particularly Saltpetre or Potassium Nitrate – the gun powder, and remained so atleast till the beginning of 20th century. Wild animals such as Tigers, Lions, Rhinos were being shot and hunted more efficiently than ever before and all the more sadly, in tens of thousands.

The British learnt the trick of the trade (of hunting) from the local kings and chieftains. By late 1700s till early 1800s, the British were laying the foundations for their rule in ‘Hindustan’ and remained mute spectators, many a times to being guests of the princely hosts. Slowly, by 1830s and 40s, the British not only took over the scene, but also imposed a ‘code’– restricting local people from hunting. As a matter of fact, the indigenous people living in the forests indulged in subsistent methods, while the British and the Maharajas would later go on to indiscriminate lengths to hunt the majestic animals roaming the forests of India.

The colonial code and the practice also enabled the British to restrict big game hunting to Maharajas and the Britishers themselves. The British also started criminalizing the indigenous tribes, to benefit them in many ways. One, it would lend support to their imperial rule by stating that ‘Hindustani’ are a bunch of savage and barbaric people. Two, the code would allow them to displace the locals – pastoralists, gypsys, nomads, indigenous tribes etc (who now couldn’t subsist on the forests anymore) and then the British would destroy forests paving way for the plantations and estates.

Lions were hunted more easily, because of the habitat in which they lived – the open savannas and also because of the nature in throwing back an attack when pursue, thus exposing them. By the end of 19th century, hunting drastically reduced the lion numbers, so much that they only existed in the princely state of Junagadh; the historic range that once spread till even modern-day Bihar and Bengal.

Slowly, a different problem then emerged. Inept hunters were unable to shoot and kill tigers, but left them injured and maimed. As a result, hundreds of these tigers resorted to killing cattle, or humans; atleast this was thought so by Jim Corbett.

Tigers were branded man-eaters, problem animals, and cattle-raiders. This also allowed the Englishmen to hunt the animals, the heroics of which would be recounted in mainland England, thus elevating their fame, and also trying to secure the hearts of the revolting locals by protecting them from these unassailable brutes. Many of these stories were dramatized to portray the gallantry and skill of the hunters, also justifying the hunts; despite most hunts happening from the ‘machan’-tops with the hunter anticipating the arrival of a tiger, to a pre-killed bait or encircling the tiger from all directions and pushing it in the direction of the huntsman sitting atop a ‘howdah’ on the back of a trained elephant.

The sport of hunting the Royal Bengal Tiger (so named by the British themselves) elevated the British masculinity and also their dominance over the inviolate and untouched expanses (environment) of India. Just like during the Mughal times, hunting a tiger wasn’t just a sport, and the British wanted to be better rulers than the Mughals.

As published in National Geographic, “according to historian Mahesh Rangarajan, over 80,000 tigers…were slaughtered in 50 years from 1875 to 1925”. Imagine the expanse of the forest and the prey base probably running in millions to support that kind of numbers of the Tiger alone.

Yet, tigers reproduced and promulgated on a very healthy scale despite this indiscriminate and ruthless extermination by the British and the Indian Maharajas alike.

Did the tigers survive the onslaught by the Mughals and the British?

The Independent India chapter

India finally was independent in 1947, but the situation of tigers worsened. The sport of the nobles and the kings was now open to every individual, across the globe, who had money at their disposal. Tourism flourished and tigers were killed for trophies, at a killer pace, even by the local Maharajas.

An advertisement in the 60s read,

Shikar! The eyes of the tiger in the jungle-black night are two haunting orbs of fire. Many who have seen them have recorded the experience on the film. Others have brought the tiger home … the sportsman’s greatest trophy. A Shikar in the jungle of India is a princely caravan, with scores of servants and chefs to tend to every need, expert hunters to guide, and thrills lurk in very rustle of the leaf. Enjoy the excitement of an Indian Shikar – the beloved sport of the Maharajas. Here’s the first step. Ask your travel agent for full information and literature on Shikar or write Dept. N.Y.

– Government of India, tourism office, New York, San Francisco, Toronto.

Not understanding the grim situation then, of the tiger crisis, this advertisement surely is spine-chilling to think of, today.

Maharaja Ramanuj Saran Singh Deo of Surguja notoriously killed 1710 tigers – the highest by anybody ever; a number even more than the total number of tigers in India as late as 2010. A few other kings from the erstwhile princely states of Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan are known to have killed tigers numbering into 100s (if not thousands).

Decades of criminalizing the tribes also didn’t do well with India, either. A few reclusive tribes (individuals) resorted to poaching and selling the pelts for a living. Ofcourse, traders and middlemen made the best of the money by exporting these pelts for higher prices.

Hunting and poaching (for tiger skins only) continued unabated. In 1968, the export of skins was prohibited, legally. This created an uproar by the traders who had already received pre-orders for the pelts – which meant ‘many tigers and leopards not born yet, were destined to honour these commitments’, in the words of Mr. Kailash Shankala, the first director of Project Tiger (yet to be formed). The cost of a tiger pelt in late 60s was around 599 dollars.

In around 1969, Smt. Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India called for a ban on hunting tigers. But before the legislation could be passed, because it was the last time one could ever participate in a Shikar, more people rushed to India, and a greater number of tigers were hunted and killed in the year than an entire decade.

Tiger hunting – a lucrative business then, allegedly raking as much as Rs. 30 million, annually. Tigers were also said to be costing a capital loss of 60 million rupees as a result of the 50,000 cattle killed by the tigers. These allegations were made to contest the decision to ban the hunting, by the lobbies of fur-traders, ex-zameendars, and erstwhile maharajas. Meanwhile, pelt trade continued through various loopholes and illegal exports. For the first time, Tiger numbers started to fall to quickly and unsustainably, thanks to a century of hunting sport.

Project Tiger

It wasn’t the tiger alone that was under attack, but the habitat as well. Slowly, the forest cover began to vanish, paving way to man-made forests or monocultures for the production of tea, coffee, rubber, paper etc. Newly settled communities of farmers or labourers (for ex., from the construction of nearby dams) encroached upon the forest lands and acquired the rights to forest produce, and killed any animal that raided their crops. Cattle became a bigger threat to the forests, as it competed with wild ungulates for grass and other pastures, eventually causing a ‘habitat shift’ of the ungulates. Pastoralists started forest fires, in a bid to rejuvenate the forests, but most times, these forest fires were uncontrollable, leading to vast areas being deforested. All of this, in addition to the thousands of hectares of forests being cleared for dams, mines, roads and railway lines, and so on.

The need of the hour was not to save the tiger alone, but it’s habitat as well.

In February 1971, the high court of Delhi passed a landmark judgement banning tiger hunting. A few studies undertaken immediately pointed out to an extinction crisis, encumbered by the burden of centuries of ruthless hunting, and a rapidly falling forest cover. Project Tiger was launched in April of 1973 in a bid to save the tigers from extinction.

9 tiger reserves were formed amassing an area of 9,115 sq. Km – Palamu, Similipal, Manas, Melghat, Ranthambore, Sundarbans, Kanha, Bandipur and Corbett. These tiger reserves were brought under special protection - the concept of core (free from human activity and interference) and buffer areas (conservation-oriented land use) was introduced. Project Tiger aimed at reducing further depletion of the tiger habitats and mitigate them by suitable management and even reversing the dwindling forest cover.

Despite having been established half a century ago, half of the tiger reserves in the above list, to this day, hardly have any tigers left. While tigers still continued to thrive in the inviolate forests (even outside the 9 tiger reserves and undocumented), a new era of poaching began, for Traditional Chinese Medicine.

The Chinese Demand

Till 1968-71 when hunting and export of tiger parts was legal, India didn’t have any idea about the demand for tiger parts in China.

Tiger was (and still is) a cultural symbol and revered in many parts of China, for its prowess and magnificence. The stripes on the forehead of a tiger seem to represent the character Wang (王)which is Chinese for King. Tiger is one of the prominent animals in art, astrology, folk tales, and even warfare in China.

Owing to their skull shape (different from that of other subspecies), it is supposed that South China tigers are the relict population of the ancestor of the modern-day tiger.

The historical range of South China tiger is much lesser even when compared to the present-day range of the Indian Tiger. In 1905, there were an estimated 20,000 tigers in China, according to German zoologist Max Hilzheimer. Since 1920s, a growing number of trophy hunters from around the world hunted down these magnificent beasts that the number fell to an estimated 4000 by 1950.

Further, during the Great-Leap-Forward campaign by Mao Zedong in 1958, South China Tigers were declared cattle-raiding vermin and hunted down. The Communist party paid a bounty of 30 Yuan per pelt (tiger skin) to the hunters. In addition to increasing human population and decreasing forest cover, tigers were extensively poached and their parts used in Traditional Chinese Medicine; so much that the tigers in the wild were exterminated, despite a delayed response to save tigers by the government.

The South China tiger became functionally extinct. There are just 70 captive tigers all born from 6 wild tigers captured in 1950s, with plans of reintroducing in the wild. But the issues of low genetic variance remain. If an epidemic, for example, sweeps through the population with a low genetic variance, the entire population is prone to a risk of extinction.

Belinda Wright in her book ‘Through the tiger’s eyes’ provides a vivid account of the consignments of Tiger and other big cat skins and parts being confiscated in the illegal trade capitals – Delhi and Calcutta. In 1992 census, only 17 tigers were counted at Ranthambore. The department denied this low number and maintained that there were 44 tigers. After a series of investigations till the mid of the same year, it was found that 20 tigers have been poached since 1989.

Today, to cater to the needs of TCM, pelts, and for selling ‘wine’ from tiger bones, sautéed meat in restaurants, countries such as China, Vietnam, Thailand and Laos have Tiger farms, where tigers are reared only to be killed (for the above markets). Hundreds or perhaps thousands of Tigers are harvested for bones, skins, organs and even meat.

The Chinese opulent class would still prefer a wild tiger (a pure bred) than one raised in captivity; and such animals are available in and hence the demand for tiger pelts and other parts hasn’t fallen even today. In 2008, in a survey conducted in six major cities, a majority of people believed that parts of wild tigers were more effective than farmed ones. Farming of tigers (or legalizing trade of animal parts) also stimulated demand by making the product legal, from a consumer viewpoint. It also made it hard for wildlife enforcement officials to distinguish the sources (farmed or wild).

Part-II

Animal or man, sovereignty over a territory is the linchpin of that individuals’ capacity, control and competency. Since the days of the Mughals till the days of free India, from hunting to poaching, for controlling men and territories to hunting for sport, tigers were killed ruthlessly. But all these are the tangible factors – the elements that are responsible directly for the loss of tigers.

A number of demographic, social, economic, political – intangible factors too destroyed or are destroying the remnant population of the tigers.

The Tribe predicament

A tiger needs only three things for its survival – prey-base, water and contiguous forests. But the forests are not entirely inviolate. This inviolate nature is not because of a single factor; there are factors and there are promulgated factors (like the one single factor everyone buys – tribal settlements)

The rights of the forests in India has been a big predicament since ages and the tribals contested with all their might. The criminalization of tribes by British was the proverbial nail in the coffin. Yet, the tribes who subsisted for centuries in these forests fought for their rights either through nonviolence methods (like the Chipko movement) or guerrilla warfare.

The aboriginals have long back realized the importance of ecosystems and contested for the rights as they witnessed the exploitation of the natural resources by the feudal kings and the Englishmen. For example, “Jal – Jangal – Jameen” was the slogan of an Adivasi movement and coined by Komaram Bheem, fighting the Nizams of Hyderabad and the Zameendari system for complete rights on and of forest resources to the Adivasis (meaning first-inhabitant or aboriginal). Like Komaram Bheem, a Gond, many aboriginals have fought for water, forests and lands (as the slogan says) since colonial era or even dating before. The aboriginals have been a part of the forest like the numerous species of flora and fauna that inhibit the forests.

The independent India did away with the British rule, but many erstwhile colonial practices were still followed such as the ‘code’ implemented by the British to minimize the rights and to displace the forest dwellers; the problem was further compounded by the contractor system (which is still prevalent to this day) – commercial logging operations were given a green-go and swathes of forest land were commoditised and auctioned to contractors for linear-development and irrigation projects, industries, mining and so on.

Notified under article 342 of the constitution, there are around 700 different tribes in India, with a few overlapping communities across states and quite a few single-tribal-population numbers running into tens of thousands.

As per the 2011 census, the tribal population stood at 104.3 million which amounts to 8.6% of the Indian population. But the disempowerment since the colonial times continues, so much that, for example, the tribals represent around 50% of the people displaced by the construction of dams, since 1947.

The hapless tribes are displaced if the government announces a development project and are also displaced if the government intends to create inviolate forests; under the promise of a socio-economic upliftment. But do they really want it? Would they prefer to co-exist in a forest? Will they continue their sustenance models if they decide to co-exist? Are all questions that nobody can answer.

The Rural predicament

These 104.3 million indigenous tribes aside, an estimated 150 million (2011 census) more people live in and around the forests of India. While many tribal communities still follow a subsistence or even a symbiotic method of resource usage, which they have been doing for many centuries, a good number of tribals and non-tribals have shifted to other means of living.

A human population of India at 17.7% and a cattle population at 19%, of that of the world, depends on the just 1% of the forest of the world (Though Indian forests cover stands at 1.75%, a crown density of around 40% is available only in 1% of the forests).

A study undertaken in Western Ghats shows that loss of forest in a protected area is 32% lower in than in non-protected areas. However, where local populations are higher, protected areas are 70% more likely to lose forest cover than non-protected areas. Also, higher population densities could have been the result of an already degraded forest due to intensive conversion and usage of forests and encroachments.

Illegal encroachments and trespassing are the reasons for most human-tiger conflicts happening in the fringes. 13,155 sq. Km of forest has been encroached, since independence. Encroachments happen in bits and pieces across forests which not only fragment the forests but also have a wider circle of influence of anthropocentric activity thus limiting the animal activity.

The population of tigers always radiates outwards. By the age of two years, female cubs takeover a part of mother’s territory, while male cubs disperse away from their natal territories. These younger males (or sometimes females) cannot challenge the resident tigers and hence are ousted. Sometimes, a few older tigers are vanquished from their own territories or move out to seek easier prey such as cattle. Tigers often come across grazing cattle, shepherds guarding the cattle, villagers defecating in the open, and so on. Barring a very few cases where Tigers could possibly ambush and hunt down humans as prey, tigers generally don’t attack humans deliberately. But tigers do kill and even feed on humans opportunistically, escalating the human-tiger conflict scene.

If the forest department doesn’t intervene or delays the compensation, villagers resort to poisoning water holes, thus killing tigers (and other animals). Poisoning is one of the leading causes of deaths, next only to poaching and infighting; around 10-15% of tiger deaths each year are reportedly because of poisoning by villagers.

Each state and tiger reserve has its own set of unique problems. For example, Maharashtra has a high incidence of electrocution of tigers (farmers electrifying their fields, with lines drawn from the nearest transformer or high-tension electric line, to save fields from wild boars or deer). Fearing prosecution in such cases, most owners bury the carcasses of tigers that die due to electrocution.

Pilibhit Tiger Reserve was in news recently over an outlandish trend. As per a report by Kalim Athar of the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB) that has been submitted to the NTCA (National Tiger Conservation Authority), in the villages of Pilibhit, elderly members of the family are sent into the forests, so that they become a deliberate prey to the tiger. If the death happens in the core area, the bodies are relocated to the nearby fields, to claim compensation from the government (Compensation is not paid, if a human being is killed inside the Tiger Reserve; the death has to happen in a human habitation, such as a crop field or buffer area).

Cattle rearing in many tiger reserves is a major intangible anthropocentric activity that is exerting extreme load on the fragile ecosystems, specifically in the fringe areas, causing habitat degradation either through haphazard grazing or trampling of the grass and as a result displacing prey (generally herbivores) from the forests, and also increasing the scope of diseases such as Foot & Mouth (FMD) and anthrax. Additionally, abandoned and stray cattle are wreaking havoc. The number of stray cattle is gauged at 5 million (urban + rural). 1/3rd of the green fodder available for cattle is grazed from forests. Cattle grazing is so rampant in certain Tiger reserves that big cats vanished from these forests (do understand that a big cat vanishing from a forest is due to years of neglect and multiple other anthropogenic factors). For instance, Palamu Tiger Reserve, has a high incidence of cattle grazing and though being of the 9 earliest Tiger reserves with an aggregate area of 1,130 sq. Km, has just 5 tigers; down from 50 tigers when it was formed in 1974. Tiger reserves like Palamu are isolated tigerscapes; there is no influx or outflux of tigers owing to a plethora of issues such as development projects, human habitations blocking the migration corridors.

It would be very unjust to push the blame onto rural and not the urban areas. As per the 2011 census, there are 53 cities which have a million population, in India. A rise in population exacts a rise in need. For instance, electricity needs are increasing day by day, and with more than 70% of the country’s demand coming from Coal via the Thermal Power Plants, and a great amount of coal lying right beneath the tiger forests, once the coal in the existing mines is exhausted, there is no need to guess where we will look for the next coal mine. Additionally, the thermal power industry’s annual water draw is estimated at 25 billion cubic metres, which is more than half of India’s total domestic water needs. That’s the onus on natural resources, exerted by humans.

Human population is undoubtedly a factor influencing the health of a forest, but not the only or the major reason for the detrimental effects. A major burden lies with development in green areas. But how are green areas and forests earmarked for development, when there are so many laws, acts, regulations, green tribunals, wildlife boards etc., to safeguard the forests? Part of the answer lies in the definition of a forest.

The Forest Predicament

The textbook definition of forest in itself is an ambiguity. Forest Survey of India (FSI) provides a biannual assessment of forest cover, by preparing thematic maps at 1:50,000 scale using remote-sensing satellites and aerial photography. As per the ISFR-2019 report, total forest and tree cover of the country is 807,276 square kilometres (which is 24.56 percent of the geographical area of the country), which is an increase of 5,188 sq. Km over the 2017 assessment.

Is the forest cover really increasing? What does forest cover actually mean?

Prior to 2016, Forest is either defined by dictionary definition or land recorded as a forest on any government record as per a 1996 Supreme Court order.

By 2016, Forest had a new definition, as below. The area is known as ‘Total Forest Cover’ which means,

-

- Already recorded forest areas.

- Patches classified as forests under state laws and land classification systems, such as chote jhad ke jungle, bani, oran, civil soyam land etc.

- Geographical features such as gair mumkin pahad, ravines, nala etc. and even mangroves, alpine meadows and montane bamboo brakes etc.

- In states with forest area less than 1/3 of the geographical area, land patches having 10 per cent crown density will be termed forest.

- In states with demarcated forest area more than 1/3 of the geographical area, land patches having 40 per cent crown density will be termed forest.

- Private plantations (upwards of 5 hectares) with more than 70% of natural forest will also be considered a forest.

This basically means that forest cover includes all man-made plantations, estates and monocultures. The definition is dangerous because not only does it create monocultured patches, but also eradicates natural ecosystems, despite a mandated compensatory afforestation elsewhere.

Using the loopholes in the archaic and amended laws, most development projects are given the nod, even in fragile ecosystems, which is the single biggest reason for wiping out of large and contiguous swathes of forests.

So, what exactly is the area of forest lost, in totality?

The Development Predicament

The most important clause of ‘legality of forest cover’, when it comes to development projects – Forest department while issuing a letter for clearance, specifically states “legal status of diverted forest land shall remain unchanged” even after the forest is cleared. Because, when a mining is completed, the cleared patch of land is filled up and returned to the forest department. Because, an irrigation project is still an area for fishing and tourism with a control by forest department.

But actually, how much forest is cleared in independent India? According to the Central Government data (such as Indian State of Forest Report), between 1951 and 1980 - 42,380 sq. Km of forest was diverted for development projects. The Forest Conservation Act enacted in 1980 made it difficult to divert forests, but still 15,000 sq. Km of forest was diverted for development projects for around 24,000 development projects since, with 1/3rd of the diverted land, around 5000 sq. Km, being given to mining alone. All in all, since independence, 57,380 sq. Km of forest was diverted to development projects. For a measure, 40, 340 sq. Km is the total core area of all the tiger reserves combined, in the present.

All development projects not limited to irrigation, hydel, railways, highways, and quarrying, destroy several hundreds of square kilometres of ecosystem in addition to fragmenting the forests, displacing indigenous tribes and destroying the corridors – not just those of tigers, but of every megafauna, in addition to. For ex., the Ken-Betwa linkage is supposed to irrigate 6 lakh ha of land, produce 75 KW of electricity and supply drinking water to 13 lakh people, but this linkage will also displace 60.17 sq. Km of core Critical Tiger Habitat of Panna Tiger Reserve and a loss of 105 sq. Km due to submergence and fragmentation of the forest; apart from adversely affecting the sustainability and the conservation efforts of the Ken ‘Gharial’ Sanctuary.

In 1951, there were 5 cities with a million-plus population, and by 2011, there were 53 such cities. With an increase in number of cities, there is an industrial growth and to move people and goods, linear infra needs to be developed.

New road ways and railways are constructed through forests. Existing ones are expanded on a war-footing, with scant regard for forests and natural ecosystems. Telecommunication, electric and pipelines (oil and water) are laid, water canals are dug, fences are erected blocking the natural wildlife corridors.

Linear development is killing other megafauna as well. Highways run across 40 and railway across 21 of the 88 identified elephant corridors. Railways alone kill 17 elephants on an average every year, mostly from the North Eastern part of India such as Odisha, West Bengal and Assam. 15% of the deaths of the critically endangered Great Indian Bustard are attributed to collision with high voltage power lines that criss-cross their flying routes. Studies also show there is a two-fold increase in extraction area of bush-meat, when roads pass through forests, in addition to fragmenting forests.

Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) has granted Environment Clearances (ECs) to 2115 projects between July 2014 and March 2020. Of these, 278 projects are less than 10 Km away from the Protected Areas (PAs). An additional 1175 projects are less than 50 Km away from the PAs, which means all these projects are severely impacting (or going to impact) the natural habitats and the migration corridors of various megafauna.

The development is coming at the cost of global or local extinction of animals and birds that include many charismatic species. So, how are these factors going to affect the present and future of tigers?

Part- III

Not a single but a combination of anthropocentric crises – the destruction of inviolate habitats and migration corridors (in addition to poaching, poisoning etc.,) is threatening the existence of tigers (and many other species).

The Tiger Predicament

From a few hundred in the 1970s to the current estimate of 3000 tigers, India did provide a fighting chance to tigers through good forest management techniques, relocation of villages from core Critical Tiger Habitats, pumping in funds for saving the tiger, some exceptional field work by lower rung staff of forest department etc.

So, is all good then? To the verdant point that numbers are increasing, yes. But this is where the veritable problem lies – accumulated advantage and isolated populations. Tiger numbers in well managed reserves are increasing, while those in many others are stagnant or are receding. And the conduits to naturally transfer the accumulated populations are ceasing to exist. The chart gives an idea about the accumulated advantage (the aphorism that rich get richer, poor get poorer) in seven states, counted between 2002 and 2018.

The disparity in numbers across the states and tiger reserves is an indication of many sorts. For example, the biggest tiger reserves don’t hold the highest number of tigers; the ones with inviolate spaces, better prey-base density etc., do. Tiger is an indicator species, an animal which talks about the health of the forest and the ecosystem. When a tiger is removed from the tiger-forest, the forest gets degraded due to a variety of factors, the major one being human-activity. Conversely, human-activity can degrade a tiger-forest when the tiger refuses to stay in that forest.

26 tiger reserves out of 50, have a population of less than 20 tigers each. These numbers have been consistent over the census period of 16 years (from 2002 to 2018). Since tigers are prolific breeders, and are sexually active from an age of around 4 years till 14 or even 15 years, with each tigress delivering around 2 – 5 cubs every two years, not only does the poor population in the 26 tiger reserves suggest that certain factors are limiting the numbers – poaching, poisoning, habitat destruction or infighting are killing tigers, but also the fact that these tigers are least connected with other tiger reserves. Absolute tiger numbers are also not very useful for the proliferation – what’s needed is a breeding population. So, the status of the 26 tiger reserves is also an indication of the falling breeding units and thus the falling tiger health of that reserve.

At around 2 years of age, the cubs separate from the mother; females take-over a part or the whole of the mother’s territory, sometimes displacing the mother or getting displaced, while males move away from the mother’s territory. Tigers undertake migrations (moving to a different place, hundreds or even thousands of Kilometres away) which benefit them in many ways such as preventing an inbreeding depression.

As already mentioned, centuries of ruthless hunting and poaching shifted the populations into single digits in many tiger reserves. Additionally, humans have blocked the traditional migration corridors creating islands with isolated populations. When tigers migrate across forests, there is an exchange of genetic material. When tigers are constricted to isolated Tiger Reserves, they will mate among themselves and create an inbreeding depression (a low genetic diversity), specifically when the isolated populations are very low.

Current populations are born from the relict and isolated population of the 1970s or the 80s, which means that atleast seven to eight generations of tigers (where ever isolated populations exist) have already been inbreeding.

In 2013, for a research paper ‘How much gene flow is needed to avoid inbreeding depression in wild tiger populations’ scientists developed a tiger simulation model and used published levels of genetic load in mammals to simulate inbreeding depression. They found that introducing tigers from different lineage to the inbred population had no effect on the population viability and that the likelihood of extinction is more than 90% over the next 20 years, specifically in isolated pockets with a very low number of tigers.

A few of the tiger reserves with populations to the order of 100 are so disconnected with others even when they are in close proximity. For ex, Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve in Maharashtra state and the surrounding forests of Gadchiroli and Brahmapuri with around 150 tigers is a couple of hundred Kms away from Kawal Tiger Reserve in Telangana state. Every year, Kawal gets a migrating population of 10-20 tigers. But they either seem to return or are poached, but they don’t prefer to stay in Kawal, which in itself is an indication of the health of the forest in terms of prey-base or water or alleviated human activity inside the forest. Tigers can migrate even thousands of Kms as proven by Walker (C1), a tiger born in Tipeshwar Wildlife Sanctuary (between Tadoba and Kawal) and that migrated to Dhyanaganga wildlife sanctuary, closer to Melghat Tiger Reserve, covering a distance of 1300 Kms over 3 months. Walker initially migrated to Kawal before retracing his route and finally settling in Dhyanaganga.

Migrating tigers generally risk running into human dominated landscapes and more often than not end up in captivity (subsequent capture and relocation) after killing one or more humans, though at most times, the kills are opportunistic. The surplus and radiating populations are also perishing – killed in infights or are branded conflict animals (for killing cattle or humans) and moved to captivity (removed from the wild) or are poached in the human dominated migration corridoes. Once a tiger is removed from the wild, it doesn’t contribute to the promulgation of the tribe anymore.

As the numbers denote, and the accumulated advantage effect, the top 10 tiger reserves will do well even in the future, containing within them a viable population of tigers. The rest?

According to a study undertaken by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), and published in 2018, 38 of the 50 tiger reserves could go extinct. As per the study, only the reserves with 20 breeding units (a tiger and a tigress) seem to have a robust future - Corbett, Kanha, Pench, Ranthambore, Bandhavgarh, Sundarbans, Kaziranga, Tadoba, Mudumalai, Sathyamangalam, Bandipur, and Nagarhole.

isolated pockets are not only facing a low genetic variance (because of no natural migration), but also fragmentation, pastoral grazing, illegal mining and timber logging, etc.

The accumulated advantage direly needs to be spread out. The connectivity with the remaining tiger reserves would not only mean a flow of surplus tigers, saving many populations but also create an exchange of genetic material (reducing inbreeding depression). Environmental clearances (both of the forests and the existing and potential migration corridors) not the laws, need to be diluted and constricted.

The Future Predicament: Conclusion

In over 150 years, the native range and the numbers of the tigers shrunk by hefty numbers. Tiger numbers are reduced by 99% of what they were, but that is not all.

Centuries of selective hunting has wiped the best of the gene pool. The bigger tigers were generally much sought-after trophies, be it in a physical form for a rug or a coat or even for a pose of a photograph. The photo records of big-game hunts of the British nobles prove beyond a reason of doubt that the tigers in those days were remarkably bigger than those of today. This is not just the case with tigers. Even in Africa, the elephants now have smaller tusks than the many that used to once. Hundreds of thousands of years in evolution, all put to waste in just one century.

Despite a known number of anthropocentric factors such as poaching, pre-emptive killing, poisoning, electrocution, human-animal conflict, diversion of forest lands to development activities not limited to industries, mining, roads, railways, canals etc., there are certain biological factors such as inbreeding depression, being prone to diseases etc., environmental factors such as floods, forest fires, cyclones (as in the case of Sundarban tigers) etc., there could be a number of stochastic processes or factors (a random process that seems to change or effect in a random way) that could severely impact long term populations of tigers.

Are we just delaying the inevitable – an extinction? In 1980s, scientists had already predicted the same, that by 2020, tigers will go extinct. But today, we are still 3000-tiger strong. All the mathematical and biological models predicting an extinction were wrong. I am sure that those scientists would have be more than happy to be proven wrong.

Today, the crisis is escalating. Unlike all those decades before 1980 when a lone factor was responsible for decimation such as big-game hunting, poaching, etc., today, multitudinous challenges lie ahead – population demographics, development, environment, human-tiger conflict, boom in tiger population in a few tiger reserves and doom in many others, etc.

In a country the size of India, the absolute numbers don’t mean anything. If each and every inch of the forest is not saved, tiger forests will vanish, corridors will be wiped and tigers might continue to exist in a handful of fenced (physically or psychologically) and isolated national parks.

If the current trends (accumulated advantage effect) continue, the tiger that once roamed the entirety of the Indian subcontinent will not be the free-ranging animal anymore.

Part - IV

The Dynamics of a Tiger Reserve

Because Tigers are territorial and they need an undisturbed habitat with water and good prey-base, the population always radiates [1] outwards (infighting between tigers happens for territory, but most try to avoid confrontations through physical – for ex. showing aggression or psychological behaviour – for ex. claw marking of trees).Two years after the cubs are born, they leave the mother in search of independent territories. Females carve a territory out of their mother’s, known as philopatry [2]. Males disperse [3] away from mother’s territory and establish their own elsewhere.

In their territory Tigers are sympatric [4] with other carnivores such as Leopards and Dholes, having a substantial dietary overlap. When tiger population increases, they compete for the same resources thus pushing out leopards and dholes – intraguild competition [5] or killing them – intraguild predation.

In the meanwhile, forests continue to shrink, with a majority of the chunk getting cleared [6] for development projects, industries and for mining [7] minerals such as coal. Additionally, tiger reserves (and other open forests and scrub lands) are also prone to illegal quarrying [8]. The laying of roads not only fragment forests but also increases the scope of poaching [9] (by two times as per studies). Irrigation projects [10] not only inundate existing ecosystems (again causing fragmentation) but also impacts hydrological cycle.

The proximity of villages to and encroachment of forests not only increases the risks of conflict but also causes pest animals [11] (population uncontrolled due to the absence of an apex predator) such as wild boars to destroy the agricultural fields – one of the primary subsistence modes. Cattle grazing (both feral and domestic) in the forest causes a habitat shift [12] of natural ungulate or herbivore population and ultimately leading to the shift in predatory population as well. Local populations also heavily depend on the forest produce [13] and in places with high human population, the dependency becomes unsustainable. Human and cattle population also increase the scope of conflict [14], with the radiating numbers of tigers.

Because tigers need undisturbed habitats, as the number or size of human habitations increase, the circle of influence [15] too increases, thus causing further fragmentation. Certain tiger reserves also have places of worship such as temples [16] that attract lakhs of pilgrims every year (who walk on feet to reach these temples inside the core critical tiger habitat - CTH). To maintain the inviolateness or the contiguity of forests and to reduce human interference, villages inside core CTHs are relocated [17] with compensation paid for the affected villagers.

A number of reasons such as unavailability of prey, surplus tiger population in core areas (pushing the younger or older tigers to the peripheries), search of a mate, human interference etc., cause a tiger to migrate [18] to greener pastures (many overcoming roads, villages or towns, mines and so on, as most migration corridors are congested or blocked due to human activity).

Part – V

The Value of a Tiger Reserve

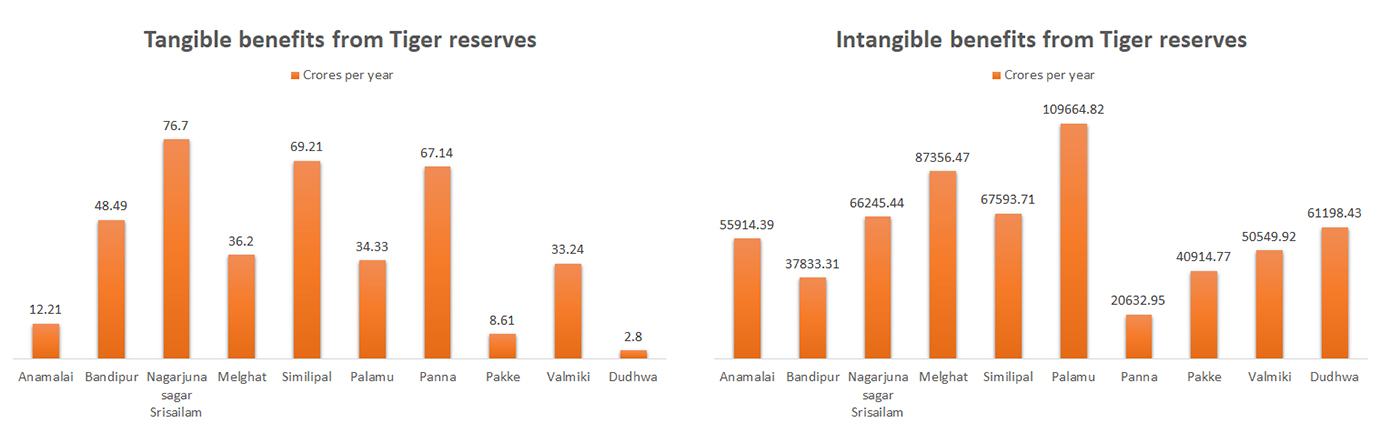

A 2019 report by the Centre for Ecological Services Management (CESM), Indian Institute of Forest Management, Government of India that conducted the study in 10 tiger reserves shows the direct and indirect benefits of a Tiger Reserve. Tiger Reserves provide tangible benefits such as employment generation, fishing, fuel wood, fodder, timber (stock & flow), bamboo, non timber forest product, nursery function, cultural heritage, recreation, tourism, research, education and nature interpretation, and intangible benefits such as habitat for species, gene-pool protection, carbon storage, carbon sequestration, water provisioning, water purification, soil conservation/sediment retention, nutrient retention, biological control, moderation of extreme events, pollination, gas regulation, waste assimilation and climate regulation.

The below is an excerpt from the report.

The study findings indicate that the monetary value of flow benefits from the selected ten tiger reserves range from Rs. 50.95 to 162.02 billion annually. These tiger reserves also conserve enormous stock of timber and carbon which is valued in the range of Rs. 137.46 billion to 967.45 billion. The stock serves as a basis for the natural systems to flourish and emanate flow of ecosystem services. The per hectare values of these TRs fall in the range of Rs. 0.41 million to 0.74 million per year. The study findings also indicate that a sizeable proportion of flow benefits (as well as stock) are intangible and hence are often unaccounted for in the socio-economic scenario and policy formulation. Economic valuation helps in recognizing these benefits and internalise them into policy actions.

It is not hard to understand the benefits from the remaining tiger reserves of India as well.

Save the Tiger should now be read as Save the Tiger Forest

Part – VI

References & further reading

Introduction - Predicted Pleistocene–Holocene range shifts of the tiger

Mughal Chapter – A concise history of Tiger hunting in India

British Chapter – Big-Game Hunting and Conservation in Colonial India by Vijaya Ramadas Mandala

The Chinese demand – Through the Tiger’s eyes, by Stanley Breeden and Belinda Wright | Poaching for Chinese markets pushes tigers to the brink | India’s hidden tiger poachers

Project Tiger – Saving Wild Tigers, by Valmik Thapar

Tribal Predicament – Claiming indigenousness in India | Forest Rights Act, 2006

Rural Predicament – Parks protect forest cover in a tropical biodiversity hotspot, but high human population densities can limit success | Grazing business shrinking potential tiger reserve | What made rural India abandon its cattle in droves | Jharkhand’s lone reserve turning into cowshed

Forest Predicament – Indian State of Forest Report (2019) | Marginal increase in India’s forest cover is masking massive deforestation | Land diverted for mining and agriculture inflates India’s total forest area | Evolving story of India’s forests

Development Predicament – Evolving story of Indias forests | Land diverted for mining, agriculture inflates India’s total forest area | Ken Betwa project could hit wildlife | Great Indian Bustard nearing extinction due to high voltage lines | Why trains keep killing elephants | Development ups the risk of Tiger extinction by 50 percent in protected areas

Tiger Predicament – Why tiger population in India is increasing | Tiger Reserves of India | Status of Tigers in India – 2018 (official report) | Tigers in 41 tiger reserves could go extinct : study

Value of a Tiger reserve – Economic valuation of tiger reserves in India